The Precedents of the Unprecedented “Takeover” Of The Capital

The Associated Press today was alarmed: President Trump’s “takeover” of Washington, D.C. was “unprecedented.” While the shock is certainly warranted, federal troops have been called in to police or shut down the District many times before. This time, in fact, would be the tenth time in our history, and the third in the just the past five years.

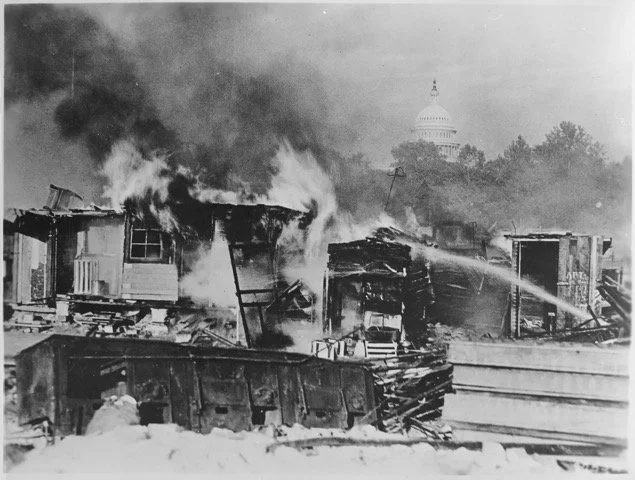

In 1932, District police killed two veterans in the name of reducing a little homelessness. (National Archives)

· In 1783, it quelled “The Pennsylvania Mutiny.”

· In 1814, it fought the British on its way to burn the White House.

· In 1861, federal soldiers mobilized there to protect the government at the beginning of the Civil War.

· It hit the streets in 1913 to monitor the apparently unarmed Women’s Suffrage Parade and in 1917 during apparently unarmed tensions escalating from race riots in St. Louis.

· There was indeed a race riot in Washington in 1919 that required federal troops to control.

· The Martin Luther King riots in 1968 attracted almost 12,000 federal troops and 1750 National Guardsmen.

· Three years later, the May Day anti-Vietnam war protests first inspired then-attorney general Mitchell to called for “preventive detention” of protesters as the they entered the District and then 10,000 federal troops to watch them when they got there.

· And the pace of U.S. military interventions in the U.S. Capital, once again, had recently picked up. In 2020, 5,000 guardsmen arrived during the George Floyd protests. Twenty-five thousand National Guardsman eventually showed up to guard against President Trump’s supporters attack on the Capitol Building. And then, last week, the same president ordered 800 guardsmen to figure out how to take over the District police force to roust, once again, the homeless as well as a hard-to-verify increase in crime.

But the most egregious example of fabricated motives and out-of-the-blue aggression against innocents in the Capital so far was the federal attack on the destitute and homeless veterans who marched to Washington in the depths of the Great Depression.

Famous Long Ago: What it looked like

July 28th

Shelters were suddenly on fire along Pennsylvania and in the parks.

National Archives

In 1932, perhaps the Depression’s worst year, an estimated 20,000 destitute and largely homeless veterans of World War I from across the United States converged on Washington in search of help. Many brought their families with them and, under strict rules of passive resistance and disciplined behavior adopted from their old military days, they planned to lobby Congress for money they’d been promised.

Their original idea was essentially to sit on the steps of the Capitol until Congress agreed to pay them a bonus that wasn’t due to be paid until 1945, thirteen years hence.

Sympathies even for veterans who are homeless were no less ambivalent than today, and most local and government officials were no more welcoming.

In Washington, rumors were quickly planted that the veterans were communists, criminals and altogether objectionable. They panhandled and looked like poor, underfed, desperate people, a generally unattractive state. J. Edgar Hoover, director of what would be re-named the FBI later that year, warned that 400,000 armed veterans from surrounding states were ready to join the “Bonus Marchers’” attack. Some, Hoover noted, were “people with Jewish features” and “Negroes.” Crime was sure to soar. Their makeshift camps in half-demolished buildings and parks were made of tin, boxes, scraps of lumber, some tents, old roofing, and barrels. Sanitation was also makeshift and a health hazard.

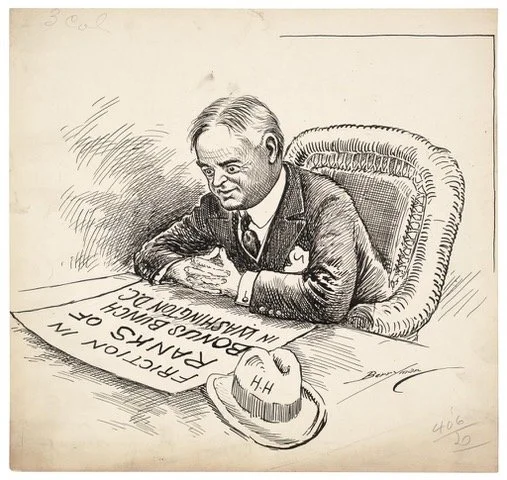

General Douglas MacArthur, then Army Chief of Staff, said the phenomenon had “more than a whiff of communism” about it. The government had yet to manufacture words like “entitlement,” but President Herbert Hoover argued that it’d be unfair to help only this one group of needy Americans when there were so many other needy groups around.

Not everyone was hostile.

The veterans’ distress moved philanthropists (including the woman who owned the Hope Diamond at the time) to pitch in money, food, clothing and more to help. The American Red Cross and the American Legion refused to help, but Pelham D. Glassford, a former general who was then the District’s police chief, strenuously helped arrange some rudimentary sanitation, food donations, and shelter.

Glassford’s bosses, however, objected. Today, the former commander of an artillery unit during the war would be called a snowflake. He urged President Hoover to wait until Congress voted on the bonus again before running them out of town. Whether the bonus passed or was defeated, the veterans were sure to leave town voluntarily. His bosses eventually fired Glassford for his heresy and his efforts.

The president, the District commissioners, the attorney general, the cabinet secretaries did wait, but for something to justify attacking and rousting the veterans.

The president waits for an excuse to drive veterans out of Washington.

(National Archives)

In mid-June, the House of Representatives voted to pay the bonus, but the Senate defeated the bill. Many of the veterans headed home but some 17,000 remained. The government’s patience thinned some more.

July 28th, 1932, was a ginned up deadline to begin demolishing some of the government-owned derelict buildings where anywhere from 40 to 140 refugees were camping. (Actual demolition, according to the contractor, couldn’t start until at least the end of the year.) The police moved in first, met some resistance, and killed two of the veterans.